Even without Osama, Afghan end game not in sight

(* This article first appeared on POREG)

The ‘killing’ of Osama bin Laden by the US special force inside Pakistan has provided yet another opportunity to tireless analysts across the spectrum to crystal gaze the evolving situation in the Af-Pak region. The general consensus is that while euphoric speeches and statements would continue to emanate from various sections of the US establishment obviously with an eye on domestic audience, cool headed decisions would be taken soon in the background. One such decision, according to many analysts, would be to enhance the intensity of negotiations with the remnant Taliban factions.

According to a recent report appearing in the Washington Post, for instance, the US administration officials think that it would be now easier for Mohammad Omar, the leader of the largest Taliban faction, to break his group’s alliance with al-Qaeda, a key U.S. requirement for any peace deal. In their view, Osama bin Laden’s death could make peace talks a more palatable outcome for Americans and insulate President Obama from criticism that his administration was willing to negotiate with the terrorists.

This is neither breaking news nor startling development. Since 2008, there have been several signals from the US administration that it is willing to hold talks with the Taliban. With the Afghan war, in spite of tactical gains by the NATO and ISAF forces, showing no signs of ending soon and substantial reduction of American armed presence by 2014 being the declared policy of President Obama, it is but natural for Washington to become eager to try out other options particularly as the relations with the Hamid Karzai’s government have deteriorated. In 2010, according to one source, a small number of officials in the Obama Administration—amongst them was Richard Holbrooke, the Special Representative for Af-Pak—argued that it was time to try talking to the Taliban again. Since then contacts with the Taliban have become a key development.

On its part, the desperate Karzai government is also trying out every possible option to come to some sort of settlement with the so called liberal factions of the Taliban. Secret parleys have been reported with the Riyadh and Islamabad playing their role to perfection as key interlocutors. According to Hamid Gul, who as Director-General of the Inter-Services Intelligence (1987-89) played the role of mid-wife at the birth of the Taliban, these Islamists have grown from strength to strength; they largely benefitted from the failure of Operation Anaconda (in 2003) and the fiasco of Operation Mushtarik at Marja in Helmand province. They have become more confident and their ranks have swelled to around 50,000 fighting men.

In a recent interview with World Security Network President Dr. Hubertus Hoffmann, Gul commented: “Now that they are sensing victory their (the Taliban) morale is extremely high. Increasingly the Afghan population is turning to them as an alternative to Karzai’s corrupt and incompetent administration.” There is a ring of truth in the Gul speak.

The Taliban’s return to power in Afghanistan, if it happens, is hardly going to be a smooth affair even if they completely de-link themselves from the al-Qaeda network. The rump Taliban groups are splintered, riven with factions, and scattered with no clear hierarchy. The Quetta Shura Taliban (QST) is the most important group. The remnants of the former Taliban government manifested as QST in 2002.

According to several documents published by the Taliban between April 2008 and May 2009, the Taliban have created additional councils to perform specific tasks. The Quetta group is led by Mullah Omar himself. Another group, the Tehrik-i-Taliban Pakistan (TTP) is an umbrella front bringing together the Pakistan Taliban and several resistance organisations and terror groups. The other major faction is the Haqqani network set up by Jalaluddin Haqqani.

The Haqqani network has sway over several south-eastern provinces in Afghanistan. It also enjoys substantial control in North Waziristan in Pakistan. Various factions of Taliban, in all probability, have de facto control in large parts of Pashtun dominated eastern and southern Afghanistan. They know that the ‘waiting’ is going to be beneficial. Hence the signals from the top leadership that they are not interested in serious negotiations as long as foreign military forces remain in Afghanistan.

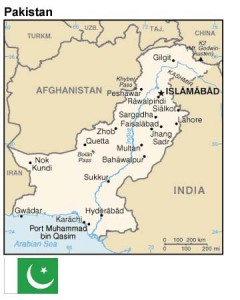

The United States, on the other hand, in all probability would insist on retaining certain key military bases in Afghanistan, particularly in the South even if there is substantial withdrawal of ground forces in 2014. Such bases will give Washington some edge in dealing with Tehran. Will Pakistan go along with the US plans or will it use its strategic leverages for a new double game?

The killing of Osama bin Laden at Abbattobad has pushed relations between the two countries to an all time low. It could turn out to be a temporary phenomenon.

Pakistan is strategically too crucial for the USA to be abandoned or pilloried at this juncture. Moreover, given the sour relationship between the Obama administration and the Karzai government, Afghanistan is hardly in a position to take advantage of Pakistan’s discomfiture.

So, the point is the endgame is still not in sight. The removal of Osama bin Laden removes a symbolic stumbling block which might encourage a spate of negotiations with the Taliban remnants. Since the Taliban are no longer a monolith and are split into multiple factions, dialogue with these Islamists is bound to be tortuous. Also the prospects of a quick breakthrough and the return of the Taliban to Kabul seem remote.

Ultimately, much would depend on the manoeuvring capacity of the Pakistan and Afghan governments and their ability to influence the US of America.(POREG)

(*The author is Convenor, Academic Committee in the Institute of Foreign Policy Studies, University of Calcutta)

-

Book Shelf

-

Book Review

DESTINY OF A DYSFUNCTIONAL NUCLEAR STATE

Book Review

DESTINY OF A DYSFUNCTIONAL NUCLEAR STATE

- Book ReviewChina FO Presser Where is the fountainhead of jihad?

- Book ReviewNews Pak Syndrome bedevils Indo-Bangla ties

- Book Review Understanding Vedic Equality….: Book Review

- Book Review Buddhism Made Easy: Book Review

- Book ReviewNews Elegant Summary Of Krishnamurti’s teachings

- Book Review Review: Perspectives: The Timeless Way of Wisdom

- Book ReviewNews Rituals too a world of Rhythm

- Book Review Marx After Marxism

- Book Review John Updike’s Terrorist – a review

-

-

Recent Top Post

-

NewsTop Story

What Would “Total Victory” Mean in Gaza?

NewsTop Story

What Would “Total Victory” Mean in Gaza?

-

CommentariesTop Story

The Occupation of Territory in War

CommentariesTop Story

The Occupation of Territory in War

-

CommentariesTop Story

Pakistan: Infighting in ruling elite intensifies following shock election result

CommentariesTop Story

Pakistan: Infighting in ruling elite intensifies following shock election result

-

CommentariesTop Story

Proforma Polls in Pakistan Today

CommentariesTop Story

Proforma Polls in Pakistan Today

-

CommentariesTop Story

Global South Dithering Away from BRI

CommentariesTop Story

Global South Dithering Away from BRI

-

News

Meherabad beckons….

News

Meherabad beckons….

-

CommentariesTop Story

Hong Kong court liquidates failed Chinese property giant

CommentariesTop Story

Hong Kong court liquidates failed Chinese property giant

-

CommentariesTop Story

China’s stock market fall sounds alarm bells

CommentariesTop Story

China’s stock market fall sounds alarm bells

-

Commentaries

Middle East: Opportunity for the US

Commentaries

Middle East: Opportunity for the US

-

Commentaries

India – Maldives Relations Nosedive

Commentaries

India – Maldives Relations Nosedive

-

AdSense code