Mirza Jaane Jaanan Shaheed: The poet Mystic

A lesser known dargah in the old city of Delhi is that of the eighteenth century poet mystic Mirza Jaane Janan. Mevlana Rumi is believed to have predicted Mirza Jaane Janan’s birth 500 years earlier in the verse:

A lesser known dargah in the old city of Delhi is that of the eighteenth century poet mystic Mirza Jaane Janan. Mevlana Rumi is believed to have predicted Mirza Jaane Janan’s birth 500 years earlier in the verse:

Jaan e dar awwal mazhare dargah shud

Jaane jaan an khud mazhar e allah shud

Descendants of the great Islamic scholar Abu Hanifa, Mirza Jaane Janan Sahaheed’s ancestors migrated in the early sixteenth century from Taif near Mecca to Turkey. Some family members accompanied Humayun to India, serving as officials in the Mughal court.

Born in 1699, Mirza Mazhar Jan-i Janan is a major figure in Naqshbandi Sufism in Northern India. His father Mirza Jan served as both mansabdar, revenue collector and as Qazi, under Emperor Aurangzeb. Upon resigning from these posts, Mirza was travelling back to Agra from the Deccan when Mirza Mazhar was born in Kalabagh, in the district of Malwa. Jan-i Janan received his initial education under the tutelage of his father while living in Agra.

Jan-i Janan unequivocally declares that “prior to the birth of Islam, God had indeed sent Prophets to India” and that their activities have been recorded in the holy books of the Indians.

After completing his education, he became a disciple and khalifa of Sayyid Nur Mohammed Badayuni, a Naqshbandi Sufi. Later, he was educated in both the conventional and the religious sciences, from the most prominent scholars of his time. After completing his education at the age of thirty, Jan-i Janan shifted to Delhi where he established his own centre of learning, appropriately called Khanqah-i Mazhariyya. He stayed in Delhi until the end of his life.

Surprisingly, unlike other Sufis of the orthodox Naqshbandi order, the Shaykh took a liberal view of Hinduism declaring, ‘After much investigation and research, what one finds out from the ancient books of the natives of India is that at the birth of the human species, God had sent a holy book by the name of Veda for the correction of their world through an angel called Brahma, who is an instrument of the creation of the world. This book comprised of four sections and it contains injunctions on the differentiation of right from wrong and information about the past and the future. They have divided the ancient history of the world into four parts and each part has been given the name ‘jug’, and for every jug the correct method of practice has been derived from each of the four branches of their holy scripture.”

Jan-i Janan took an important step in representing Hinduism as a monotheistic tradition. He declared that all Hindu sects believe in the unity of God as the transcendent creator who creates out of nothing and they believe that the world is created. He wrote that Hindus affirm and believe in the annihilation of the world, in rewards and punishments for good and bad deeds, in resurrection and accountability in the hereafter. In perhaps his most generous moments of writing, Jan-i Janan renders a sweeping approval of ancient Indian systems of knowledge by declaring that the Hindus have a commanding grasp over the rational and traditional sciences, ascetic practices, spiritual practices, and mystic unveilings. He insisted that the rules and regulations of Hinduism were entirely harmonious and coherent.

Jan-i Janan argued that idol worship represented a form of meditation and explained that the practice is similar to the practice of the Muslim Sufis who meditate upon the image of their masters for purposes of spiritual healing

Jan-i Janan took on the arduous task of clarifying and defending the practice of idol worship among the Hindus. He argued that idol worship represented a form of meditation directed towards certain angels that exist in this world of corruption because of God’s command; or the spirits of certain perfect individuals who exist in this world even after having abandoned their bodily forms; or certain living men whom the Hindus perceive as immortal like the figure of Khizr in the Muslim tradition. By concentrating their thought on these representations, Hindus could create a spiritual connection with the entities represented by them and they thus attain their material and spiritual needs.

He explained that the practice is similar to the practice of the Muslim Sufis who meditate upon the image of their masters for purposes of spiritual healing; the only difference being that Muslims do not make a concrete representation out of their masters.

He wrote that the idol-worship of the Hindus bears no resemblance to the belief systems of pre-Islamic pagans because they used to regard their idols as independent agents, effective by themselves and not as instruments of divine power.

On the question if Prophets were ever sent to India, Jan-i Janan adopts a particularly bold stance by unequivocally declaring that “prior to the birth of Islam, God had indeed sent Prophets to India” and that their activities have been recorded in the holy books of the Indians.

He explained that from the remains of the Hindu books, it seems that they had attained the stages of perfection and completion and that the general mercy of God did not forget the humanity of this vast landmass. Since prior to the arrival of prophet Muhammad, all nations in the world were sent Prophets and each nation was only obliged to follow the message of its particular Prophet and not that of any other nation. However, after the arrival of Prophet Muhammad in the 6th century, the situation changed fundamentally. After Muhammad’s emergence, all Eastern and Western religions were abrogated and until the world is extant, no one may refrain from embracing Islam.

Mirza Jan e Janan defended the popular Hindu practice of prostration by arguing that it was out of respect and not that of idolatry, because in their religion, parents, masters and teachers are greeted not with the Muslim greeting of ‘salaam’ but with a prostration.

The poet successfully bridged the differences between religious orthodoxy and Sufism.

The mystic asserted that Shia-Sunni differences had no relevance to essential Islamic beliefs. In addition to training scores of disciples, Jan-i Janan also wrote a voluminous number of letters and treatises on various aspects of Sufi psychology, metaphysics and practice. He is most well known though for his polemical writings against the Shi’i.

In 1781, he was attacked and injured by a Shi’i in Delhi and he died three days later. He criticized the Shia tradition of perpetuating the tragedy of Kerbala on Muharram and their reverence towards replicated tombs of Imam Hussain. Reacting to such statements, an Irani, along with two accomplices, shot the Sufi with a pistol. He survived a further three days, refusing to identify the assailant at the emperor’s court. The bullet wounds led to his death on 7th Muharram 1195 Hijri/ January 1781 AD.

The poet mystic made a selection of one thousand verses from his twenty thousand Persian verses. Self-criticism is perhaps why so little of his Urdu poetry exists; much of it lies scattered in various anthologies.

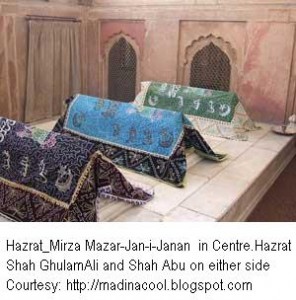

Mirza Jaane Janan is recognized as one of the four pillars of eighteenth century Urdu poetry alongside with Sauda, Mir Taqi Mir and Khwaja Mir Dard. The Sufi poet’s tomb is in the old city of Delhi.

-

Book Shelf

-

Book Review

DESTINY OF A DYSFUNCTIONAL NUCLEAR STATE

Book Review

DESTINY OF A DYSFUNCTIONAL NUCLEAR STATE

- Book ReviewChina FO Presser Where is the fountainhead of jihad?

- Book ReviewNews Pak Syndrome bedevils Indo-Bangla ties

- Book Review Understanding Vedic Equality….: Book Review

- Book Review Buddhism Made Easy: Book Review

- Book ReviewNews Elegant Summary Of Krishnamurti’s teachings

- Book Review Review: Perspectives: The Timeless Way of Wisdom

- Book ReviewNews Rituals too a world of Rhythm

- Book Review Marx After Marxism

- Book Review John Updike’s Terrorist – a review

-

-

Recent Top Post

-

NewsTop Story

What Would “Total Victory” Mean in Gaza?

NewsTop Story

What Would “Total Victory” Mean in Gaza?

-

CommentariesTop Story

The Occupation of Territory in War

CommentariesTop Story

The Occupation of Territory in War

-

CommentariesTop Story

Pakistan: Infighting in ruling elite intensifies following shock election result

CommentariesTop Story

Pakistan: Infighting in ruling elite intensifies following shock election result

-

CommentariesTop Story

Proforma Polls in Pakistan Today

CommentariesTop Story

Proforma Polls in Pakistan Today

-

CommentariesTop Story

Global South Dithering Away from BRI

CommentariesTop Story

Global South Dithering Away from BRI

-

News

Meherabad beckons….

News

Meherabad beckons….

-

CommentariesTop Story

Hong Kong court liquidates failed Chinese property giant

CommentariesTop Story

Hong Kong court liquidates failed Chinese property giant

-

CommentariesTop Story

China’s stock market fall sounds alarm bells

CommentariesTop Story

China’s stock market fall sounds alarm bells

-

Commentaries

Middle East: Opportunity for the US

Commentaries

Middle East: Opportunity for the US

-

Commentaries

India – Maldives Relations Nosedive

Commentaries

India – Maldives Relations Nosedive

-

AdSense code