Dalai Lama for ‘free election’ of his successor, Stumps China

-By MALLADI RAMA RAO

Dalai Lama addressing Tibetans at Dharmasala on on the ocassion of 52nd Anniversary of Tibetan upraising

The announcement of Tibetan spiritual leader, the Dalai Lama on March 10 of his decision to ‘retire’ doesn’t come as a surprise. The Chinese reaction was on predictable lines though he has taken the wind out of Chinese sails by calling for a ‘political’ successor.

The announcement of Tibetan spiritual leader, the Dalai Lama on March 10 of his decision to retire from active politics doesn’t come as a surprise. The Chinese reaction was on predictable lines. China termed the resignation as a ‘trick to deceive’ the world.

‘He (Dalai Lama) has often talked about retirement in the past few years. I think these are his tricks to deceive the international community,” foreign ministry spokeswoman Jiang Yu told reporters in Beijing.

But close observers of the Tibetan scene point out that there is no suddenness in the Dalai Lama’s decision. He has been speaking of the need to pass on the baton to a younger leader citing among other things his age.

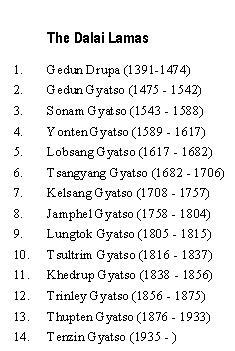

Born as Lhamo Thondup (literally Wish-Fulfilling Goddess) on July 6, 1935 to a poor peasant family in the small village of Taktser (means Roaring Tiger) in the province of Amdo, he was barely three-year old when he was ‘discovered’ at Kumbum monastery as the successor of the Thirteenth Dalai Lama, Thupten Gyatso (1876 – 1933).

“My desire to devolve authority”, the Dalai Lama said in his statement, “has nothing to do with a wish to shirk responsibility. It is to benefit Tibetans in the long run. It is not because I feel disheartened”.

Nevertheless, the timing of the ‘resignation’ is significant. It coincided with the anniversary of the ‘uprising’ in Tibet in 1959. Four days from today, Tibetan Parliament –in-exile would begin its 11th session.

The 75-year-old Nobel Peace Prize winner would like to see the ‘free election’ of his successor at the parliament session.

“As early as the 1960s, I have repeatedly stressed that Tibetans need a leader elected freely by the Tibetan people to whom I can devolve power. Now we have clearly reached the time to put this into effect,” he said in his statement on the 52nd anniversary of the Tibetan People’s National Uprising day in Dharamsala. And added “During the forthcoming 11th session of the 14th Tibetan Parliament-in-Exile which begins on March 14, I will formally propose that the necessary amendments be made to the Charter for Tibetans-in-Exile, reflecting my decision to devolve my formal authority to the elected leader.”

This picturesque Himalayan town has been his abode ever since he fled his native Tibet in 1959 after a failed uprising. The uprising was as much against the Chinese rule as for protection of Tibet’s religious and cultural values as much as it was to fight for their country.

This picturesque Himalayan town has been his abode ever since he fled his native Tibet in 1959 after a failed uprising. The uprising was as much against the Chinese rule as for protection of Tibet’s religious and cultural values as much as it was to fight for their country.

“The people of Kham, or Eastern Tibet, rose up against Chinese occupation when Communist authorities began to implement ‘democratic reforms’, the program to eliminate monastic and tribal leadership and eradicate the traditional social system,” recalls Jamyang Norbu, the author of Warriors of Tibet: The Story of Aten and the Khampas’ Fight for the Freedom of their Country ( Wisdom, Boston 1986). He estimates the number of Tibetans who died in the uprising at half a million.

Violent insurrections had taken place earlier in Eastern Tibet in Gyalthang (south of Lithang) in 1952 and also in north-eastern Tibet (Amdo) in Hormukha and Nangra. While the two uprisings took heavy toll and ‘left only a few blind men, cripples, fools and some children’ according to eye witnesses, the Khampa uprisings on the 18th day of Tibetan New Year of 1956 was truly broad based. It was well coordinated also.

The Dalai Lama, in his own words, has been a ‘free spokesperson of the Tibetan people’. He repeatedly ‘spelled out their fundamental aspirations to the leaders of the People’s Republic of China’. He was disappointed by the ‘lack of a positive response’.

Yet his counsel to the Tibetan faithful is patience. ‘….judging by the political changes taking place on the international stage as well as changes in the perspective of the Chinese people, there will be a time when truth will prevail. Therefore, it is important that everyone be patient and not give up,’ he said last year (2010).

Not withstanding his optimism, there are no signs of Beijing changing.

ATTACKS STEPPED UP On the eve of ‘Uprising’s anniversary’, and marking the third anniversary (March 14, 2008) of bloody riots in Lhasa next week, China placed restrictions on the entry of foreign tourists. Jiang Yu, the Foreign Ministry spokesperson, attributed the restrictions to ‘bitterly cold winter weather’ and ‘limited accommodation capacity’ and ‘safety concerns’. Foreign media has no free access to Tibet even during normal times; special permissions are required to visit the region.

Ahead of Lhasa riots anniversary, Chinese officials have stepped up attack against the Dalai Lama. A Tibetan Communist party official dubbed the Tibetan spiritual leader as a ‘wolf in monk’s robes’.

A former Tibet Governor Qiangba Puncog told the media in Beijing that when Dalai Lama dies, it will trigger small shock waves in Tibet but won’t result in serious instability, while the present governor Padma Choling, said the Dalai has no right to abolish the institution of reincarnation and thereby underscored the continued hard-line stance on China. He went on to add ‘Dalai Lama does not have a right to choose his successor any way he wants and must follow the historical and religious tradition of reincarnation’.

On its part, the Chinese government has been saying all along that it has to approve all reincarnations of living Buddhas in Tibetan Buddhism. China wants to sign off on the choosing of the next Dalai Lama.

In 1995, after the Dalai Lama named a boy in Tibet as the reincarnation of the

previous Panchen Lama, Beijing put that boy under house arrest and installed another in his place.”

Many Tibetans at home and exile have spurned the Chinese-appointed Panchen Lama as a fake. But will that experience stop China from naming its own successor, to the 14th Dalai Lama? If it doesn’t, it raises the possibility of there being two Dalai Lamas

Many Tibetans at home and exile have spurned the Chinese-appointed Panchen Lama as a fake. But will that experience stop China from naming its own successor, to the 14th Dalai Lama? If it doesn’t, it raises the possibility of there being two Dalai Lamas — one recognized by China and the other chosen by exiles or with the blessing of the current Dalai Lama.

The Tibetan Buddhism has a history of more than 1,000 years, and the reincarnation institutions of the Dalai Lama and Panchen Lama have been carried on for several hundred years.

The Dalai Lama appears conscious of the possibilities. A reading of his statement on his successor makes this clear. He is not asking selection of a spiritual successor. He is asking for the selection of a political successor. And he wants the selection to be through a free election by Tibetan Parliament –in- exile.

POLITICAL SUCCESSOR

Post -1956, the Dalai Lama has come to be the spiritual and political centre even as he said ‘I have no difficulty accepting that I am spiritually connected both to the thirteen previous Dalai Lamas, to Chenrezig and to the Buddha himself’. And acknowledged the ‘repeated and earnest requests both from within Tibet and outside, to continue to provide political leadership’.

His campaign against Chinese repression is both political and diplomatic in nature.

For instance his latest statement says: ‘The Chinese government claims there is no problem in Tibet other than the personal privileges and status of the Dalai Lama. The reality is that the ongoing oppression of the Tibetan people has provoked widespread, deep resentment against current official policies. People from all walks of life frequently express their discontentment. That there is a problem in Tibet is reflected in the Chinese authorities’ failure to trust Tibetans or win their loyalty. Instead, the Tibetan people live under constant suspicion and surveillance. Chinese and foreign visitors to Tibet corroborate this grim reality’.

Turning to reform, he has this to say: ‘One of the aspirations I have cherished since childhood is the reform of Tibet’s political and social structure, and in the few years when I held effective power in Tibet, I managed to make some fundamental changes. Although I was unable to take this further in Tibet, I have made every effort to do so since we came into exile. Today, within the framework of the Charter for Tibetans in Exile, the Kalon Tripa, the political leadership, and the people’s representatives are directly elected by the people. We have been able to implement democracy in exile that is in keeping with the standards of an open society…’

So the Dalai Lama’s desire to devolve formal authority to the elected leader is bound to stump the Chinese. Because an elected leader will be much more free to articulate the aspiration of the present day Tibetans in exile.

By facilitating the process, the 14th Dalai Lama may be achieving his predecessor Thupten Gyatso’s goal for Tibet’s modernization.

-

Book Shelf

-

Book Review

DESTINY OF A DYSFUNCTIONAL NUCLEAR STATE

Book Review

DESTINY OF A DYSFUNCTIONAL NUCLEAR STATE

- Book ReviewChina FO Presser Where is the fountainhead of jihad?

- Book ReviewNews Pak Syndrome bedevils Indo-Bangla ties

- Book Review Understanding Vedic Equality….: Book Review

- Book Review Buddhism Made Easy: Book Review

- Book ReviewNews Elegant Summary Of Krishnamurti’s teachings

- Book Review Review: Perspectives: The Timeless Way of Wisdom

- Book ReviewNews Rituals too a world of Rhythm

- Book Review Marx After Marxism

- Book Review John Updike’s Terrorist – a review

-

-

Recent Top Post

- NewsTop Story Record Pentagon spending bill and America’s hidden nuclear rearmament

-

NewsTop Story

Taliban Suffers Devastating Blow With Killing Of Minister

NewsTop Story

Taliban Suffers Devastating Blow With Killing Of Minister

-

China NewsCommentaries

Reality Shadow over Sino-American ties

China NewsCommentaries

Reality Shadow over Sino-American ties

-

CommentariesNews

Ides of trade between India and Pakistan

CommentariesNews

Ides of trade between India and Pakistan

-

CommentariesTop Story

Palestinians at the cross- roads

CommentariesTop Story

Palestinians at the cross- roads

-

CommentariesTop Story

While Modi professes concern for the jobless, “his government’s budget escalates class war”

CommentariesTop Story

While Modi professes concern for the jobless, “his government’s budget escalates class war”

-

CommentariesNews

Politics of Mayhem: Narrative Slipping from Modi ….?

CommentariesNews

Politics of Mayhem: Narrative Slipping from Modi ….?

-

Commentaries

Impasse over BRI Projects in Nepal

Commentaries

Impasse over BRI Projects in Nepal

-

CommentariesNews

Yet another Musical Chairs in Kathmandu

CommentariesNews

Yet another Musical Chairs in Kathmandu

-

CommentariesTop Story

Spurt in Anti-India Activities in Canada

CommentariesTop Story

Spurt in Anti-India Activities in Canada

AdSense code