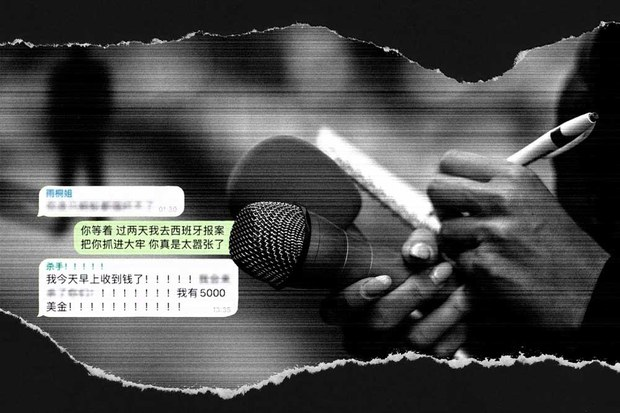

For female journalists, covering China comes at a cost

The strange men started showing up at Su Yutong’s Berlin apartment in early June. For weeks, one or two would arrive each day.

Su grew up in China but since 2010 has lived in Germany, where she works as a journalist, including for Radio Free Asia. Her visitors, though, thought they were visiting a prostitute.

“Almost every day different people rang my doorbell,” Su said. “They say they are here for an Asian woman, looking for sex.”

The fake escort ads were just part of the abuse Su says she’s experienced over the past 10 months. Bomb threats tied to reservations under Su’s name at hotels in Berlin, Houston and Hong Kong that she didn’t make prompted calls from local police.

A fake Twitter account with her name and the word “bitch” was created. She’s been threatened with doctored nude photographs and forged receipts from adult stores. She said hackers tried to access her social media and bank accounts.

In November, German police told her to leave her apartment after she received rape and death threats, apparently from one particularly aggressive harasser over Telegram. For a time, she said she felt a wave of nausea around strange men in public, though more out of embarrassment than fear, she said.

“I don’t know what other things they will do to harass and threaten me, but it has … really affected my life,” Su said.

A target for harassment

Su says she’s been a target of abuse since leaving China in 2010 to live in exile in Germany and continue her work as a reporter. The name-calling and threats and other harassing behaviors picked up, though, after she attended an event to commemorate the 1989 Tiananmen Square massacre in June.

She has filed several complaints with the German police. One official initially told Su her case seemed like the work of a particular individual, a singular stalker.

But there is evidence of a broader conspiracy, and Su fears her harassers could have links to the Chinese government — an anxiety shared by other reporters of Chinese descent who have also faced abuse.

Last fall, Su told her editors at RFA about what she was facing. RFA decided to publish her story along with other accounts to show what it can be like to report on China at a time when its officials are intent on protecting the country’s image and extending its global reach.

German police are investigating Su’s case but have refused to comment further.

A request for comment from the Chinese Embassy in Germany from RFA has not been answered.

A price to pay

Globally, harassment of women in the media is commonplace.

Almost 70% of female journalists have experienced some form of abuse in relation to their work, according to a survey by the International Women’s Media Foundation and Trollbusters, a group that monitors online harassment.

A report released in 2022 by the Australian Strategic Policy Institute (ASPI), a Canberra-based think tank, said the harassment of female journalists of Asian descent who report critically on China can be particularly aggressive — and appears to be increasing.

The sheer volume of vitriol targeting reporters given China’s size and the nationalistic fervor of many of its citizens can set the abuse apart. Compounding their anxiety is a fear that the intimidation is sanctioned, if not coordinated, by the Chinese Communist Party itself.

“When, for example, an American female journalist gets trolled, it’s probably coming from right-wing crazies or some fringe corner of society,” said Vicky Xu, a journalist in Australia, whose reporting on abuses against Uyghurs in Xinjiang brought a flood of death threats. “The kind of role and voice they have is very, very limited.

“The harassment of Chinese journalists like myself is mainstream. It’s a mainstream position that is encouraged by the state.”

State-backed trolling?

The ASPI report listed journalists covering China for The Wall Street Journal, The Economist, The New Yorker and The New York Times as victims. At least some of the offending posts are likely linked to the Chinese government, ASPI concluded. Accounts that had promoted CCP policies pivoted to harass the journalists, the report found.

Posts include graphic online depictions of sexual assault, homophobia and racist imagery and life-threatening intimidation, said Albert Zhang, a co-author of the report.

The people who harassed Su told her they supported the Chinese government and warned her against speaking or reporting critically on Beijing. Whether the harassers in Su’s case are overzealous supporters of the CCP acting on their own or are part of an official operation isn’t entirely clear.

But the intent behind this kind of harassment is the same: “to silence the view of these women and also serve as a deterrence against others reporting critically on China,” Zhang said.

‘Psychological torture’

As a reporter and researcher at ASPI, Xu helped expose how the supply chains of major companies, including Apple, Nike and Adidas, may have benefitted from forced Uyghur labor in Xinjiang.

For her work, Xu said she was called a slut, a traitor and a demon on Twitter.

A 2021 report in the Global Times, a CCP mouthpiece, called her a “morally low person” and suggested she was putting Chinese nationals living in Australia at risk by contributing to anti-Chinese sentiment.

She had to close her LinkedIn, Instagram and Twitter accounts after they were bombarded with threats, shutting her off from an important outlet for journalists.

It all felt like “psychological torture,” Xu told RFA. An outgoing, part-time stand-up comic, Xu began to isolate herself, keeping away from friends and family. She said that her health suffered for months.

“People congratulate me and they say that this work is really important, and that I changed or inspired legislation,” Xu said. “But the flip side of that is the Chinese government also noted the success and influence of that report, and they made me pay a price.”

Sexism strains

China watchers say that reporters from China can be viewed as threats for their ability to see behind the veil of secrecy the CCP tries to maintain through its own heavily censored media. They speak the language, know the country’s history and have sources in China to help them understand what goes on behind the scenes.

Male journalists who report on China face abuse too, but the women say that the strains of sexism that go unchecked in Chinese society and online culture in general make them more frequent targets.

“I tweet, but I never go on Twitter, because there is just too much crap,” said Yaqiu Wang, a senior China researcher at Human Rights Watch who has written about harassment against critics of the CCP.

Wang said she can expect hundreds of nasty comments for every Twitter post she writes that references China but doesn’t bother to read them.

“I don’t want to read 200 comments about people saying that I’m a traitor.”

Harassers – in the flesh, on the phone

When Su attended the June 4 Berlin commemoration of the Tiananmen Square massacre as a reporter, she said a middle-aged Chinese man walked up to the protesters and began taking pictures.

Two days later, at around 5 a.m., she received a Telegram message of a doctored photograph made to look like a naked picture of her with the caption, “Who’s this?”

The person who sent the message said Chinese exiles shouldn’t amplify China’s shortcomings.

An organizer of the event told RFA that she was also contacted by the same account. Both she and Su blocked the number on Telegram. Su has no idea how the person got her number.

A day or two later, random men started appearing at Su’s apartment.

She did not answer the door, but in exchanges with them in German, they indicated they were looking for sex, and believed her to be a sex worker.

A friend of Su’s who RFA spoke with witnessed one encounter in August. The man ran when Su threatened to call the police.

Bomb threats and fake ads

In October, Su reported for RFA on a harassment case involving Wang Jingyu, a young dissident who was living in exile in the Netherlands.

After the report, Su told RFA that another man started to harass her, including by reserving hotel rooms and then later calling in bomb threats under her name. He threatened both Su and Wang over texts and video messages and told them that he supported the CCP.

RFA is not naming him because his identity cannot be confirmed and efforts to reach him were unsuccessful.

The man showed Su and Wang a receipt of an electronic money transfer that he purported to be from a Chinese handler and told Su that this person had directed him to post the doctored adverts about her as a sex worker on internet sites in German – the adverts that presumably brought the random men to her door.

The harasser later sent Su forged documents, including a receipt for sex toys, that he threatened to post on a Twitter account in an effort to publicly shame her.

“I am actually very conservative. I have never been to nightclubs,” Su said. “I can never imagine myself getting related to prostitution and sex services,” she added, noting how important her Christian faith is to her. “This is fatal to me.”

A directive to move

She and Wang reported the harassment to police. After that, the abuse grew worse.

In November, the harasser threatened to rape and murder Su, at which point the German police told her to vacate her apartment.

She is now staying with a friend.

Police declined to comment to RFA, other than confirming that “an investigation into suspected threats is being conducted by the Berlin police under the case number you provided.”

Dirty messages

Sheng Xue, an author and journalist who fled China after Tiananmen and now lives in Canada, said she’s faced harassment similar to Su. Sheng worked at RFA for 17 years but is now a freelance journalist and writer.

In 2014, she said online ads offering sex were posted with her name and cell phone number in cities across North America. She would get calls at her home from New York and San Francisco.

The harassment isn’t constant, she said, but ebbs and flows with important dates and events, including the anniversary of Tiananmen Square or the 2008 Beijing Olympic Games.

Last September, with the approach of Chinese National Day, Sheng said she received hundreds of comments on Twitter, many of which were accompanied by nude photographs doctored with her image.

“They always use this kind of very dirty message,” she said.

Return to society

Xu, the journalist in Australia, said a pornographic video falsely purported to depict her surfaced online, as did a fake documentary about her sex life.

More recently, she has also faced efforts to physically intimidate her. In October, Xu said she noticed a man standing outside her apartment, watching her.

“When I tried to film him, like really up close, he didn’t look at me. He didn’t flinch. He just walked away,” Xu said.

She said she kept isolated behind a number of security safeguards she set up in response to the threats.

But Xu has since re-emerged into society. She’s also taken inspiration from the women who led the recent “white paper” protests that pushed China to rescind its restrictive zero-COVID policies, although many have since been arrested.

Xu is learning to live with the strange men who sometimes follow her, is adept at spotting hacking attempts, and carries on when her public speeches are interrupted by “CCP fanatics.”

“I don’t feel safe, but I’m not going to stop what I do because I don’t feel safe,” she said.

More harassment, and a response

It’s been weeks since Su has heard from the harasser who forced her out of her apartment. A Facebook page set up in his name stopped being active after Feb 9.

But Su said she continues to get abuse.

On Feb. 11 and 12, she received a flurry of calls concerning hotel bookings and/or bomb threats made in her name in Hong Kong, Macau, Istanbul, New York, Houston and Los Angeles.

Su told RFA that hotel employees told her that the reservations included deposits, indicating the perpetrators had some measure of financial resources. A screengrab from her phone reviewed by RFA shows unknown calls throughout the night.

The day before, Su said a stranger texted and offered to pay her cash to stop her “activities.”

“I told him to f— off and blocked him,” she said.

—A RFA report, Mar 20, 2023

Copyright © 1998-2020

https://www.rfa.org/english/news/china/harassment-03202023133743.html

-

Book Shelf

-

Book Review

DESTINY OF A DYSFUNCTIONAL NUCLEAR STATE

Book Review

DESTINY OF A DYSFUNCTIONAL NUCLEAR STATE

- Book ReviewChina FO Presser Where is the fountainhead of jihad?

- Book ReviewNews Pak Syndrome bedevils Indo-Bangla ties

- Book Review Understanding Vedic Equality….: Book Review

- Book Review Buddhism Made Easy: Book Review

- Book ReviewNews Elegant Summary Of Krishnamurti’s teachings

- Book Review Review: Perspectives: The Timeless Way of Wisdom

- Book ReviewNews Rituals too a world of Rhythm

- Book Review Marx After Marxism

- Book Review John Updike’s Terrorist – a review

-

-

Recent Top Post

-

CommentariesNews

Ides of trade between India and Pakistan

CommentariesNews

Ides of trade between India and Pakistan

-

CommentariesTop Story

Palestinians at the cross- roads

CommentariesTop Story

Palestinians at the cross- roads

-

Commentaries

While Modi professes concern for the jobless, “his government’s budget escalates class war”

Commentaries

While Modi professes concern for the jobless, “his government’s budget escalates class war”

-

CommentariesNews

Politics of Mayhem: Narrative Slipping from Modi ….?

CommentariesNews

Politics of Mayhem: Narrative Slipping from Modi ….?

-

Commentaries

Impasse over BRI Projects in Nepal

Commentaries

Impasse over BRI Projects in Nepal

-

CommentariesNews

Yet another Musical Chairs in Kathmandu

CommentariesNews

Yet another Musical Chairs in Kathmandu

-

CommentariesTop Story

Spurt in Anti-India Activities in Canada

CommentariesTop Story

Spurt in Anti-India Activities in Canada

-

NewsTop Story

Nepal: Political Stability Under Threat Again

NewsTop Story

Nepal: Political Stability Under Threat Again

-

NewsTop Story

Accountability Tryst With 2024 Ballot….

NewsTop Story

Accountability Tryst With 2024 Ballot….

-

NewsTop Story

What Would “Total Victory” Mean in Gaza?

NewsTop Story

What Would “Total Victory” Mean in Gaza?

-

AdSense code