‘No public mourning for Li Keqiang’

“The people’s premier.” “Rest in peace.” “A good premier whose political career shouldn’t have ended the way it did.”

Chinese people took to social media with candle emojis and condolences to mourn the death of former premier Li Keqiang on Friday – until censors stepped in to ensure that only uniform and formulaic condolences remained for the 68-year-old technocrat, who died of a heart attack in the early hours of Friday morning in Shanghai.

Earlier on Friday, it was still possible to see personal comments from individual users lauding Li’s perceived qualities as a national leader, including a widely shared video clip of the late former premier talking about the problems faced by Chinese farmers and descriptions of him as “the people’s premier.”

But by Friday night, much of the individual content was no longer available, with only state media and official statements turning up in search results for “Li Keqiang” and related keywords.

The majority of condolences on the official state television report on Li’s sudden death by heart attack at a Shanghai hotel appeared limited to the “wishing you a good journey,” the Chinese equivalent of “rest in peace.”

The official government announcement of Li’s death on Weibo showed no comments but tens of thousands of likes and reposts, suggesting that comments had been turned off.

The official government announcement of Li’s death on Weibo showed no comments but tens of thousands of likes and reposts, suggesting that comments had been turned off.

Meanwhile, a citizen journalist account on X started posting warnings from the authorities on university campuses across the country not to post anything political online, not to use words to describe Li that were not already approved by state media, and not to leave flowers, hold gatherings or engage in any kind of public mourning, on or offline.

The X account “Mr. Li is not your teacher” posted photos of notices banning any kind of public gathering issued by officials at universities in Shanghai, in the southern province of Hainan and the southwestern province of Guizhou.

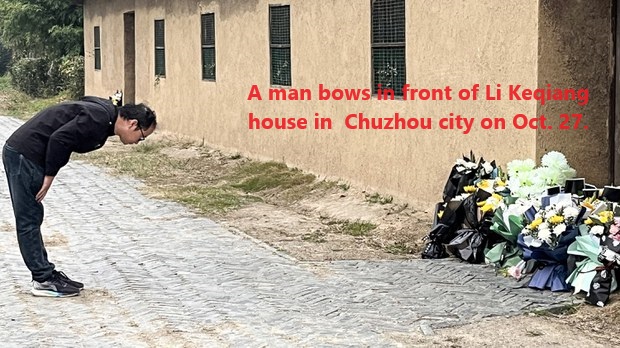

It also posted photos of yellow and white floral tributes on a street in the eastern city of Hefei, the traditional colors for a Chinese funeral.

“As night falls, more and more flowers are laid under Li Keqiang’s former residence,” the account commented.

The reported bans on public mourning for Li come less than a year after students and other young people flocked to take part in the “white paper” protests after three years of grueling COVID lockdowns.

Student union leaders in Hainan University were told to hold an emergency meeting, and not to record the proceedings, and to ban any online or offline mourning activities, including “rallies, demonstrations, floral tributes and other memorial activities.”

Ghosts of 1989

Students at Guiyang Aviation Industry Technology College were warned off posting anything online for the next few days, including comments in group chats, blog posts or livestream video. They have also been barred from talking to the media.

“If any harmful speech occurs or material is disseminated, it will be transferred to the judicial authorities for serious handling,” the message warned, according to a photo posted by “Mr. Li is not your teacher.”

Staff at Shanghai Jiaotong University were ordered to “immediately get in among the students, pay attention to their thoughts and opinions at this time, and resolutely ban any inappropriate remarks, online or offline.”

“Pay attention to students’ movements over the next couple of days … and to any gatherings or mourning activities on campus,” the notice said.

Li isn’t the first Chinese premier to die suddenly of a heart attack.

In April 1989, thousands flocked onto Tiananmen Square in a mass public outpouring of grief over the sudden death of widely loved premier Hu Yaobang. Those gatherings developed into a weeks-long mass pro-democracy movement ending in a massacre of civilians by the People’s Liberation Army.

According to late Communist Party official Bao Tong https://www.rfa.org/english/news/politics/china_15th-20050201.html, who was in government at the time: “The whole nation was plunged into grief. In a commemoration that took its cue from that for [former premier] Zhou Enlai, the students began making their way to Tiananmen Square in silence.”

“In 1977, people were ostensibly mourning for Zhou, but in fact were turning out against Mao. In 1989, they were ostensibly mourning for Hu, but things were even more complicated. Not only was Hu a former General Secretary who had presided over the throwing out of thousands of trumped up criminal cases, but he was also a politician who was kicked out for falling foul of [late supreme leader] Deng [Xiaoping].”

An era of ‘turmoil’

Similarly, the initial outpouring of public grief for Li Keqiang was more of a reflection of public dissatisfaction with life under ruling Chinese Communist Party leader Xi Jinping than an endorsement of Li’s performance as premier, according to current affairs commentator Si Ling.

“A lot of people are trying their best to express their condolences or have discussions about Li Keqiang in various online spaces,” Si said. “It’s like a [collective] sigh over the current difficulties in today’s China, and about pessimism over the country’s future.”

“Li Keqiang’s death has become a symbol, and an excuse for people to vent serious dissatisfaction with the status quo,” he said.

Financial commentator Xiang Xiang said China’s internet users can tell without being told that keyword searches related to Li’s death have been classified as having “major political or social sensitivity” by the Chinese government.

“Any discussion of Li Keqiang’s merits or faults is totally prohibited,” Xiang said.

Instead, readers are directed by keyword search results to state news agency Xinhua’s official obituary and other state media content.

Si said the topic is particularly sensitive as it comes after China’s defense minister Li Shangfu and foreign minister Qin Gang were removed from their posts in relatively quick succession. Neither had been long in office.

“A series of personnel changes at the highest levels of the Chinese government have reminded people that the current era is one of … turmoil,” he said, adding that comparisons with the death of Hu Yaobang in 1989 are inevitable.

“He also handed over the reins of power and then died shortly after leaving office,” Si said. “People started to hold public memorials, which led to the 1989 democracy movement, throwing the Chinese government into turmoil for a long time to come.”

“Even though Li Keqiang lacks Hu Yaobang’s political pedigree or historic status, the Chinese government would rather kill a thousand by mistake than let one go free.”

“Any chance that history might repeat itself will be completely nipped in the bud,” Si said.

-RFA report, Oct 27, 2023

https://www.rfa.org/english/news/china/premier-death-censorship-10272023141513.html

-

Book Shelf

-

Book Review

DESTINY OF A DYSFUNCTIONAL NUCLEAR STATE

Book Review

DESTINY OF A DYSFUNCTIONAL NUCLEAR STATE

- Book ReviewChina FO Presser Where is the fountainhead of jihad?

- Book ReviewNews Pak Syndrome bedevils Indo-Bangla ties

- Book Review Understanding Vedic Equality….: Book Review

- Book Review Buddhism Made Easy: Book Review

- Book ReviewNews Elegant Summary Of Krishnamurti’s teachings

- Book Review Review: Perspectives: The Timeless Way of Wisdom

- Book ReviewNews Rituals too a world of Rhythm

- Book Review Marx After Marxism

- Book Review John Updike’s Terrorist – a review

-

-

Recent Top Post

-

Commentaries

Impasse over BRI Projects in Nepal

Commentaries

Impasse over BRI Projects in Nepal

-

CommentariesNews

Yet another Musical Chairs in Kathmandu

CommentariesNews

Yet another Musical Chairs in Kathmandu

-

CommentariesTop Story

Spurt in Anti-India Activities in Canada

CommentariesTop Story

Spurt in Anti-India Activities in Canada

-

NewsTop Story

Nepal: Political Stability Under Threat Again

NewsTop Story

Nepal: Political Stability Under Threat Again

-

NewsTop Story

Accountability Tryst With 2024 Ballot….

NewsTop Story

Accountability Tryst With 2024 Ballot….

-

NewsTop Story

What Would “Total Victory” Mean in Gaza?

NewsTop Story

What Would “Total Victory” Mean in Gaza?

-

CommentariesTop Story

The Occupation of Territory in War

CommentariesTop Story

The Occupation of Territory in War

-

CommentariesTop Story

Pakistan: Infighting in ruling elite intensifies following shock election result

CommentariesTop Story

Pakistan: Infighting in ruling elite intensifies following shock election result

-

CommentariesTop Story

Proforma Polls in Pakistan Today

CommentariesTop Story

Proforma Polls in Pakistan Today

-

CommentariesTop Story

Global South Dithering Away from BRI

CommentariesTop Story

Global South Dithering Away from BRI

-

AdSense code