Violence Returns to Pakistan’s Major Cities

STRATFOR

At dawn July 12, militants raided a prison guard residence in Lahore, Pakistan, leaving nine staff members dead and three more wounded. The Tehrik-i-Taliban Pakistan quickly claimed responsibility for the attack, saying the guards had mistreated prisoners who were members of the Pakistani militant group. The raid came just three days after militants ambushed an army camp in the district of Gujrat, killing seven soldiers and one police officer who were searching for a missing helicopter pilot. The Tehrik-i-Taliban Pakistan also claimed that attack.

Over the last two years, Pakistan has had something of a respite from dramatic attacks such as those that plagued the country from 2007 to 2010. During those years, a series of high-profile and highly disruptive attacks against police, army and intelligence targets challenged the government’s ability to control the country. The attacks occurred in Pakistan’s most populous province, Punjab, in cities such as Lahore and in the capital, Islamabad.

While suicide bombings and attacks in Pakistan’s troubled northwest (along the border with Afghanistan) have continued apace since 2010, major attacks in Pakistan’s Punjab-Sindh core have essentially ceased. The sole instance of dramatic violence involving government targets outside of the northwest since 2010 was an attack on a naval station near Karachi following the death of Osama bin Laden.

Despite the break from violence in Pakistan’s major cities, many of the same conditions present during the wave of attacks from 2007 to 2010 remain. Another escalation in violence is very possible, especially in Pakistan’s volatile climate and with elections coming up.

Timing of the Attacks

The two attacks (along with numerous other attacks and an attempted assassination) came the week after Pakistan formally reopened NATO supply routes through the country to Afghanistan. The supply routes had been closed for more than seven months after a deadly cross-border attack by U.S. forces in November that killed 24 Pakistani soldiers. The day the routes reopened, the Tehrik-i-Taliban Pakistan told journalists it would attack trucks carrying NATO supplies in protest.

But rather than an impetus for attacks, the reopening of the supply line is more likely a political opportunity for the Pakistani Taliban militants to promote anti-American sentiment in Pakistan. The NATO supply line is one of the most visible products of the U.S.-Pakistani relationship. The Tehrik-i-Taliban Pakistan and some political opposition groups have criticized the Pakistani government for helping Washington while the U.S. military conducted strikes killing mostly Pakistanis along the border with Afghanistan. By opposing the NATO supply line, the Pakistani Taliban militants are able to generate popular support across Pakistan.

The seven-month closure of the supply line gave NATO and the United States a chance to prove that they can use the Northern Distribution Network to bypass Pakistan. During the shutdown, there was no evidence in Afghanistan of an attempt to exploit the closed route, so it is hard to argue that the Afghan Taliban (or their Pakistani peers) gained any material advantages from the shutdown. If anything, the Pakistani Taliban militants can benefit from the supply route’s opening; the trucks are easy targets for looters and can provide revenue and supplies for militants in Pakistan’s northwest, and the militants can exact extortion payments from transportation companies.

The Tehrik-i-Taliban Pakistan’s real motivation for resuming attacks in Punjab after a two-year hiatus is more complicated than the reopening of the NATO supply line. It involves a remote geographic region of Pakistan that has been dragged into the 10-year-old Afghanistan War, a struggling Pakistani economy, distrust of Pakistan’s current government and upcoming elections that are seen as an opportunity to address grievances against Islamabad. Most of these grievances are the same complaints that drove the violence from 2007 to 2010, when militant activities in Pakistan peaked. Since 2009, however, military forces have moved into many of the militant havens in Pakistan’s northwest, denying the Pakistani Taliban forces sanctuary. But this is not a permanent solution to Pakistan’s internal rifts.

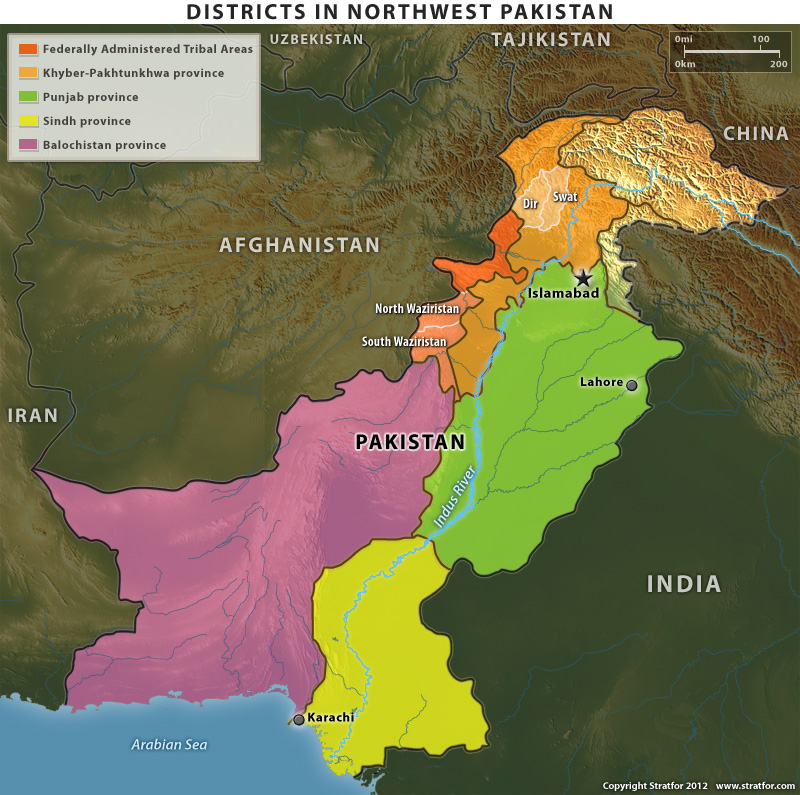

The Tehrik-i-Taliban Pakistan is based in the province of Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa and the Federally Administered Tribal Areas in the Pakistani northwest. During the Soviet-Afghan war in the 1980s, Pakistan and the United States used Islam as the ideological motivation to rally militias in the border region to oppose the Soviet occupation. The United States turned its attention elsewhere after the Soviets withdrew, leaving Pakistan to manage a complex network of militants. Islamabad attempted to use these militants as proxies during the 1990s to exercise influence in Afghanistan and India.

But after 2001, the United States pressured Pakistan to restrain its militant proxies in Afghanistan in order to support the U.S. war against Islamist militancy. After a few years of wavering, former Pakistani President Pervez Musharraf did crack down on these groups’ leaders in Pakistan, beginning with the Red Mosque siege in 2007. It soon became apparent that the militant groups were more autonomous than believed. By 2009, radical cleric Maulana Fazlullah claimed the district of Swat as an Islamic emirate, threatening Pakistan’s territorial integrity within roughly 320 kilometers (200 miles) of the capital.

The Pakistani Taliban militants made it clear that their goal was to take over the Pakistani state, beginning in the mountains surrounding the Indus River Valley. This led the government to deploy forces to Swat in April 2010. These forces expanded their offensive to South Waziristan later that year and by the end of 2010, they had gone into every single district of the Federally Administered Tribal Areas save North Waziristan. Since the army’s operations in South Waziristan, one of the Tehrik-i-Taliban Pakistan’s strongest sanctuaries, militant attacks in Punjab have decreased.

The United States launched operations parallel with Pakistan’s, targeting Pakistani Taliban militant leaders using unmanned aerial vehicle strikes in North and South Waziristan. These strikes disrupted the Tehrik-i-Taliban Pakistan’s leadership structure and likely affected the group’s ability to organize, train and conduct attacks in Pakistan’s core. Such disruptions would certainly affect the Pakistani Taliban militants’ ability to construct and deploy very large bombs, such as vehicle-borne improvised explosive devices. The attacks in Gujrat and Lahore were both simple, involving gunmen on motorcycles. Such tactics do not require elaborate training or preparation and can be staged easily in Pakistan’s core.

Although its capabilities might be diminished, the Tehrik-i-Taliban Pakistan has not disappeared. Fazlullah recently indicated that he and his forces are intent on retaking Swat from the military. Fazlullah and his followers based in neighboring Afghanistan’s Kunar province periodically have conducted cross-border raids against military outposts in Pakistan’s Dir district. Because of the continuing threat, the Pakistani military does not appear to be anywhere close to withdrawing troops from the area. Pakistan’s chief of army staff confirmed as recently as July 7 that troops are staying in the northwest.

Between the international economic turmoil and the parallel dynamics of a democratic uprising and jihadist insurgency that led to the fall of the Musharraf regime, Pakistan has been in dire economic straits since 2008. Chronic energy shortages, high military spending related to the counterinsurgency campaign and revenue shortfalls led Islamabad to sign an $11.3 billion package with the International Monetary Fund three years ago. However, in the last half of 2011, the fund withheld the final tranche of more than $3 billion largely because Islamabad had failed to take steps to reduce its budget deficit. (At the time, Pakistan, sensing slightly better economic growth and an inability to comply with the fund’s stringent budgetary demands, decided to pursue its own fiscal reform program.)

More recently, Islamabad has been forced to return to the IMF for a new loan arrangement to keep from defaulting on the existing loan. As with other countries implementing austerity measures in order to balance their budgets and qualify for outside help, the Pakistanis are finding that applying austerity measures hurts political popularity. The Tehrik-i-Taliban Pakistan will exploit this situation by pointing out the costs of deploying tens of thousands of Pakistani soldiers to the northwest to combat militants.

Moreover, Pakistan’s supreme court is challenging Pakistani President Asif Ali Zardari on corruption charges. Zardari faces allegations that he embezzled millions of dollars from the Pakistani financial institution when his late wife, Benazir Bhutto, was prime minister.

Whether Zardari embezzled the money is somewhat irrelevant, since the case has been elevated to a political dispute between the executive and judicial branches of the Pakistani government over the limits of executive immunity and how much authority the supreme court has over the president. This is no insignificant challenge; the judicial branch politically damaged Musharraf during his presidency after he fired Chief Justice Iftikhar Mohammad Chaudhry in 2007. Zardari’s current difficulty with the supreme court indicates that the political struggles between the two branches have not been resolved. The rift opened up by the legal conflict allows other parties to gain political support at the expense of Zardari and his ruling Pakistan People’s Party.

Even though the Tehrik-i-Taliban Pakistan favors the adaptation of an extremely austere interpretation of Sharia to Pakistan’s current legal system, it is savvy enough to see a political opening and exploit it. The Pakistani Taliban militants will use Zardari’s case to paint the country’s politicians as corrupt and untrustworthy. Elections are slated for the first half of 2013 but could be held as early as the next quarter of 2012, given the mounting political crisis in the country. With the political environment in flux, this is the time for various elements to assert themselves to get attention from the political parties. The stronger the Pakistani Taliban militants can make their case, the more pressure they can put on any future government to relax military deployments in the northwest.

The Military as a Temporary Fix

Many factors in Pakistan have not changed since the spate of attacks from 2007 to 2010. The United States is still trying to negotiate the terms for its withdrawal from Afghanistan, and those terms depend on Pakistan’s ability (and willingness) to keep security in Afghanistan on its current track. The withdrawal of NATO forces from Afghanistan will create a major security crisis for Pakistan, which is weakened and is racing to stabilize its side of the border before the 2014 deadline. The United States’ negotiations with the Taliban and with Pakistan are not making much progress right now, but the sooner Pakistan can get militants along the border under control, the stronger its negotiating position with the United States will be. The Pashtun tribes along the Afghanistan-Pakistan border — the area from which the Tehrik-i-Taliban Pakistan came — will certainly want a say in matters. Without meaningful political power, these groups will use violence to negotiate with Islamabad.

And as long as there are Pakistanis displeased with the regime and the economic situation, there will be Tehrik-i-Taliban Pakistan sympathizers in Punjab who support more radical change. These individuals provide the network and motivation for continuing attacks against the Pakistani government.

Military deployments to northwest Pakistan have kept militants in check for the past couple of years (at least in Punjab state), but that is not exactly a long-term solution. The military was supposed to provide security in Pakistan’s northwest to allow the civilian administrations to regain control of the districts. However, the federal and provincial governments have made little progress in reviving civil government at the municipal and district levels in Swat and the surrounding region. Meanwhile, the military continues to battle militants in the tribal badlands for which Islamabad lacks a political strategy, relying instead on the military’s continued presence.

Domestic military deployments are rarely popular and, though sometimes necessary for short periods, eventually become self-defeating and a drain on resources. Right now, Pakistan’s military presence in the country’s northwest is backed only by a feeble government. The lead-up to Pakistan’s elections is an opportunity for the Tehrik-i-Taliban Pakistan to make its case against internal military deployments. Should Islamabad’s political will shift and the military lose its advantage in the northwest, the militants could continue their campaign in Pakistan’s core, returning to high-profile, disruptive attacks.

“Violence Returns to Pakistan’s Major Cities is republished with permission of Stratfor.”

-

Book Shelf

-

Book Review

DESTINY OF A DYSFUNCTIONAL NUCLEAR STATE

Book Review

DESTINY OF A DYSFUNCTIONAL NUCLEAR STATE

- Book ReviewChina FO Presser Where is the fountainhead of jihad?

- Book ReviewNews Pak Syndrome bedevils Indo-Bangla ties

- Book Review Understanding Vedic Equality….: Book Review

- Book Review Buddhism Made Easy: Book Review

- Book ReviewNews Elegant Summary Of Krishnamurti’s teachings

- Book Review Review: Perspectives: The Timeless Way of Wisdom

- Book ReviewNews Rituals too a world of Rhythm

- Book Review Marx After Marxism

- Book Review John Updike’s Terrorist – a review

-

-

Recent Top Post

-

NewsTop Story

What Would “Total Victory” Mean in Gaza?

NewsTop Story

What Would “Total Victory” Mean in Gaza?

-

CommentariesTop Story

The Occupation of Territory in War

CommentariesTop Story

The Occupation of Territory in War

-

CommentariesTop Story

Pakistan: Infighting in ruling elite intensifies following shock election result

CommentariesTop Story

Pakistan: Infighting in ruling elite intensifies following shock election result

-

CommentariesTop Story

Proforma Polls in Pakistan Today

CommentariesTop Story

Proforma Polls in Pakistan Today

-

CommentariesTop Story

Global South Dithering Away from BRI

CommentariesTop Story

Global South Dithering Away from BRI

-

News

Meherabad beckons….

News

Meherabad beckons….

-

CommentariesTop Story

Hong Kong court liquidates failed Chinese property giant

CommentariesTop Story

Hong Kong court liquidates failed Chinese property giant

-

CommentariesTop Story

China’s stock market fall sounds alarm bells

CommentariesTop Story

China’s stock market fall sounds alarm bells

-

Commentaries

Middle East: Opportunity for the US

Commentaries

Middle East: Opportunity for the US

-

Commentaries

India – Maldives Relations Nosedive

Commentaries

India – Maldives Relations Nosedive

-

AdSense code